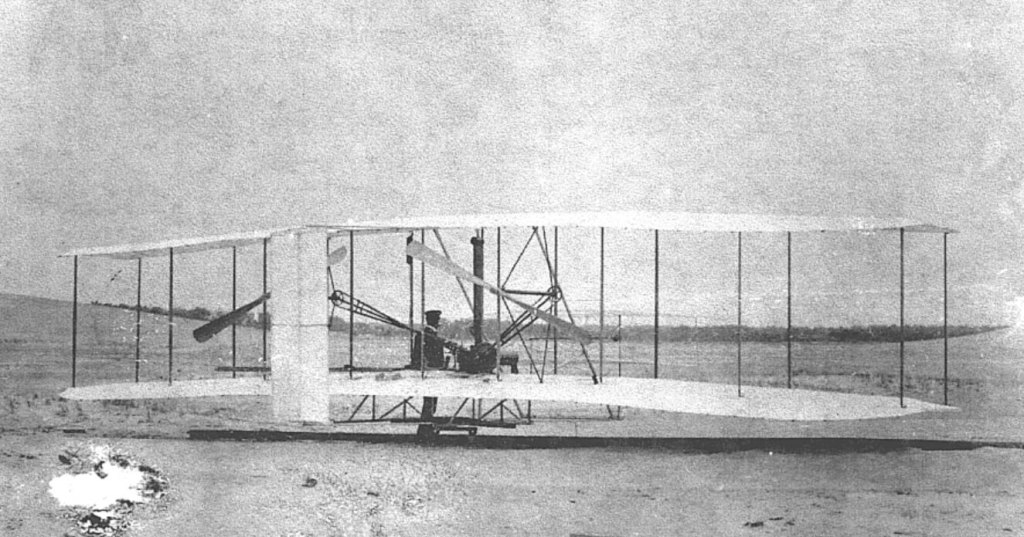

Standards, tech innovations, and rigorous flight procedures allow millions of travelers to safely reach their destinations by plane every year. What does aviation do better than healthcare? I looked closer at the safety procedures and called Airbus—and the more I learned about aircraft, the more I realized that medicine today is like flying in 1903.

How dangerous is flying vs. going to a hospital?

Patient experience and passenger experience have a lot in common: making an appointment is like buying a plane ticket, waiting in the waiting room is like waiting at the gate for boarding, and making a diagnosis and planning treatment is like navigating the trajectory of a flight. The doctors are like skilled pilots doing their best to reach the destination with possibly less turbulence—although, in medicine, the goal is the patient’s health.

I don’t like the term “patient journey”. A visit to the doctor is not a pleasant journey on vacation with free drinks on the board and sunscreen in the bag. It’s often a struggle for health. Nevertheless, medicine and aviation share many analogies that can teach us a lot.

Aviation has made impressive progress over the past two hundred years, now being a pioneer in organizational perfection and safety, delivered by training supported by breakthrough technologies. Can healthcare benchmark from the success and early pitfalls of commercial flights?

The aviation industry is based on strict safety rules to minimize accidents and mitigate their impact. The best example is the Tokyo plane crash in January 2024. All 379 passengers and crew onboard the Airbus A350 survived due to a flawless evacuation process.

The risk of being involved in a plane crash is only 1 in 1.2 million, and the risk of death is 1 in 11 million. When driving a car, the probability of a fatal accident is 1 in 5,000, 22,000 times higher. In 2022, of the approximately 3.7 billion plane passengers, only 229 fatal aviation accidents were recorded in 12 crashes. In Europe, 20,640 people died in road accidents, 808 in railway accidents, and 147 in aviation crashes.

According to WHO, one death per 1 million is caused by medication errors, which equates to 63,000 patients in Europe every year. Even though this may feel like comparing apples to oranges, medical errors haven’t been addressed effectively yet and often result from procedural mistakes and a lack of innovation.

Boarding starts at home

Back in the 1990s, buying an airline ticket involved either a visit to a travel agency or a phone reservation with a credit card number.

Today, it’s fully automated. Passengers purchase a ticket online at the airline’s portal. Before taking off, they go through the online boarding process by optionally choosing a seat, buying extras (a seat with extra legroom, a meal, a VIP lounge, etc.), and downloading the boarding pass directly to a mobile app or electronic wallet on a smartphone.

This self-service reduces queues at check-in counters and bureaucracy. Airlines recommend arriving at the airport 2 hours in advance to ensure everybody will make it on time, go through security checks, and find the right gate. The waiting time is part of the journey and serves as a safety cushion for punctuality. Still, the waiting time isn’t wasted: you can watch airplanes taking off and landing and have a coffee or lunch.

How about boarding in healthcare? The patient only books an appointment (i.e., buys a ticket), but most of the onboarding takes place at the registration desk—which can cause workflow problems.

The patient could provide some of the information at home, such as their symptoms and reason for the visit, and the healthcare facility can plan the length of the visit and additional services needed (blood pressure measurement, lab tests, etc.) ahead of time. Using AI, an onboarding system could even personalize the questions according to the data in the electronic health record as a follow-up check. Then, the data from the pre-visit symptom checking could be transferred to the electronic health record and even summarized by an AI—the doctor could save time on basic questions, while patients gain time to rethink and specify their symptoms and provide some details like results of blood pressure monitoring, etc.

The second group of organizational issues is patient no-shows and last-minute-shows.

While flying with empty but paid-for seats is not a problem for airlines, in public healthcare, missed appointments mean longer waiting times for other patients (who should be seen by a doctor urgently) and financial losses. Patients who do not pay out-of-pocket often do not cancel the visit. There are a few methods to reduce no-shows; however, all require a healthcare facility to have high digital maturity. They include multiple and automated reminders, reliable communication channels between patients and the clinic (apps with count-down features or a visualization of the preparations for the visit), a reduction to a minimum of the waiting times (hence, the patient knows when the visit will start and end), and better use of the time spent in the waiting room for necessary pre-tests or a conversation with a nurse.

There is so much more room for improvement. Healthcare slept through the smartphone revolution, while passenger aviation made the most of it.

Security is a matter of well-designed procedures supported by tech

Let’s use another simplified analogy: A doctor’s office is like a pilot’s cabin. Both pilots and doctors make decisions based on information from the environment. In the pilot’s case, it’s the flight parameters, while the doctors utilize the patient’s data.

Of course, there is one key difference: passengers know their destination well when boarding a plane, and the pilot follows a predetermined flight trajectory. There is no space for discussion. In the case of a doctor, the treatment path is, ideally, mutually worked out with the patient, although the goal is clear—disease prevention and/or recovery.

Digitalization has made aviation much safer and reduced the number of accidents and incidents over the last decades. One example is the so-called fly-by-wire (FBW). These flight control systems use onboard computers to process parameters the pilot enters and then control the machine, its engines, and controls. The system calculates the control surface positions required to achieve that outcome.

Another critical safety innovation is the terrain awareness and warning system (TAWS) to prevent collisions with the terrain, which used to happen quite often, even in aircraft piloted by an experienced crew. The breakthrough came in the 1970s when Don Bateman developed a device in the cockpit that automatically warned pilots if their aircraft was approaching the ground or water.

TAWS checks the plane’s altitude and distance from obstacles several hundred times per second to determine a flight trajectory and warn if there is an obstacle in the flight path.

There are many more similar systems: an automatic runway guidance system; the Runway Overrun Prevention System (ROPS), which warns the crew that the runway may be too short to land on safely; and the Flight Management System (FMS), which calculates the plane’s trajectory in real-time, enabling pilots to make evidence-based decisions. Thank the FMS the next time you hear from the pilot how long the flight will take.

Now imagine a doctor piloting a patient: using manual switches, calculating flight parameters manually, using a paper map instead of GPS, and handling all the critical information without support. It feels like flying with the Wright brothers on their first plane invented in 1903.

The first electronic health records were developed in the 1970s. Still, doctors today must mainly rely on their own experience because they don’t have access to complete patient data collected at different points of care. What is missing are standards, willingness to share data, and the data exchange infrastructure. And perhaps one more: the vulnerability of the system to the patient harm that analog healthcare leads to. Accidents in the aviation industry caused by errors result in disasters that resonate in the media, leading to investigations and lawsuits and, ultimately, loss of revenue for aircraft manufacturers or airlines. In healthcare, these losses remain invisible.

Doctors do not have the cognitive capacity to know every patient personally and follow all the scientific papers published daily. Within a 10-minute patient visit, they do not have time to view the medical history manually in the electronic medical records. There are already solutions to improve the quality of decision-making in medicine and reduce the number of errors: Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS), AI health prediction systems, medical alert systems, and telemonitoring solutions.

However, healthcare systems lack care standards and quality measures to make these innovations widespread. Doctors act mainly individually, rarely in teams. Even when dealing with the most complex cases, they used to make decisions following intuition, an instinct that can be affected by time of day, stress, bias, and limited access to knowledge.

Pilots, in the most dangerous stages of flight—takeoff and landing—can rely on the assistance of the flight control tower. Doctors are on their own.

Health IT systems vs. pilot’s cockpits

Doctors hate their computers, while pilots adore their cockpits.

The pilot’s cockpit, packed with monitors and toggles, may look complicated at first glance. In fact, it’s a thoughtfully designed and standardized control center, whether it’s Boeing or Airbus.

Essential indicators such as speed, altitude, heading, and direction are visible in front of the pilots. They are arranged in a T-shape (for Western-built jets) to facilitate the ergonomics of control and ensure that the pilot always has the most critical information in sight. Airspeed is on the left, attitude pitch roll is in the middle, altitude is on the right, and heading is at the bottom.

The design of the switches corresponds to their role. The landing gear lever is wheel-shaped, and the landing flaps on the wing have a wing shape. Pilots perform their procedures according to a checklist. Each flight requires the participation of two pilots: the captain and the co-pilot.

In the cockpit, a rule called the “dark cockpit philosophy” applies. When no action is required, the buttons on the overhead panel are dimmed and lit when attention is needed.

Meanwhile, doctors are lost in health IT systems’ interfaces. Every developer uses its own rules for organizing information on the screen. Getting to vital patient information requires scrolling, switching between tabs, clicking, and sometimes looking for data from other sources.

Software for doctors has also expanded over the years to serve reporting and billing roles instead of serving patient care.

Automation has significantly increased safety

I asked the experts at Airbus, the world’s leading aircraft manufacturer, what healthcare can learn from the aviation industry. “Every industry should be open to learning from others” was the response.

“There are certain areas, such as adherence to procedures, clear communication, crew resource management, and the use of automation, in which aviation has made tremendous progress over the years.” And this has led to a significant increase in the safety level: in 1970, an average of 4.77 people per million passengers were killed in aviation accidents, and in 2022, it was 0.17. That’s 28 times less.

Just as in healthcare, there are a vast number of stakeholders in the aviation industry. Thus, aviation implemented international cooperation in analyzing incidents and learning lessons early. “The safety investigation of accidents and incidents aims solely at promoting aviation safety through accident prevention. It doesn’t abort blame or liability. Following the safety investigation, the published reports make it possible to share the lessons learned and may contain safety recommendations for consideration.”

Learning from each other, learning from mistakes—why does it still not work well in often siloed medicine? Medical errors are not always recorded, analyzed, and shared to drive organization and medical progress. Instead, they are often kept silent for fear of consequences. Sweeping the problem under the carpet doesn’t help solve it.

What we have here is a legal-cultural-mentality challenge.

Intuition-based decisions are deadly

Besides automation, one more factor contributed to safety: the mind-shift of cooperation.

Crew Resource Management defines the roles and responsibilities of the captain, first officer, and cabin crew. The final decision always belongs to the captain. Still, this decision must be based on all available data from other crew members and external sources—a subjective opinion when the lives of hundreds of passengers are at stake is a no-go. Many accidents in the past resulted from the crew relying solely on hierarchical decision-making.

Automation serves as an aid to the pilot, but the pilot always decides what the priority is, what route to take, and most importantly, when to take over from the autopilot.

Pilots have and will always have to follow the “Golden rules”:

- Fly, navigate, and communicate with appropriate task-sharing

- Use the proper level of automation at all times

- Understand the FMA at all times (Flight Mode Annunciator tells the crew which autopilot/flight directors/auto-thrust modes are engaged)

- Take action if things do not go as expected

Artificial intelligence helps to process massive amounts of flight data and identify operational, technical, and traffic-related potential safety risks. “AI helps to connect the dots from which a bigger picture emerges, often invisible to the human eye,” an Airbus expert says.

The focus on human factors goes beyond pure technical expertise. For example, to mitigate human performance risks, emphasis is also being placed on flight crew mental resilience training. Human pilots are not afraid of technological advances—they welcome them for the sake of safety.

Now, think about healthcare. What comes first: hierarchical decision-making or patient safety? Which approach dominates: following intuition or reliably analyzing and consulting data to avoid biases that threaten patient safety? Is medicine a team effort or working in silos?

When will healthcare finally reach new heights using the latest technology despite the challenges posed by bad weather (read: crises)?

Special thanks to the Airbus press team for helping me to complete all the relevant information and answering all my questions. I know it was an unusual interview.

Can I ask you a favor?

Please donate to aboutDigitalHealth.com (€1+) to support independent (and human) journalism. Thank you for your support!

€1.00