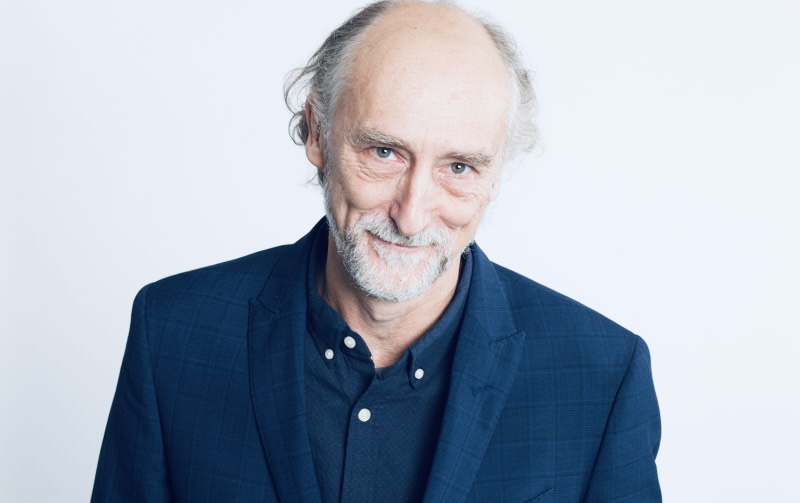

Alfonso Valencia, the Director of the Life Sciences Department at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center, leads one of Europe’s largest and most ambitious computational biology teams. I meet him in the Catalan capital to discuss the promise and peril of artificial intelligence: the power of generative models and the unease they inspire, Europe’s struggle to define its role in the global AI race, and why, in his view, quantum computing may be the next great leap.

We’ve seen a rapid rise of AI technologies in the last three years, especially generative AI. Is this the final stage of AI development, or should we expect something completely different in the coming years?

I wish I could say no, but honestly, I don’t know. It’s tough to believe that what we have now, the ChatGPT-type models, will be the ultimate stage of AI. These are, in fact, very simple technologies. What they do is essentially statistical. They do not understand the environment, the context, or the situation they’re talking about.

If this is all, then we are in trouble. These systems are, by definition, unreliable. We don’t know whether the answers produced by generative models —whether text or images —are valid or to what degree we can trust them. That puts us in a very difficult position.

Right now, we’re doing our best to make this technology useful because it’s what we have. In biology and medicine, this trust factor is essential, and much of the work goes into compensating for the technology’s shortcomings. Of course, improvements are happening in transformers and other architectures: better models, better engineering. But they don’t solve the intrinsic problem.

One of the main concerns with generative AI is “hallucination.” Companies claim to have reduced it significantly. Is this something that can be eliminated entirely?

Hallucinations are not really “mistakes” from the machine’s perspective. The system is just maximizing probabilities. But from a human point of view, when the output doesn’t match the truth, we call it a mistake. And this is intrinsic to the way the system works.

What we can do is build layers around it, checks against knowledge bases, pre-verification mechanisms, and cross-model validation. There’s a lot of engineering and a lot of money going into making these models less error-prone. And they are indeed becoming more reliable. But here’s the key: none of this removes the intrinsic uncertainty. And worse, we don’t have a good way to measure that uncertainty.

In my field, protein modeling, if you use a system like AlphaFold, the model gives you confidence levels of 80% and 90%, and those numbers are benchmarked. We can’t experimentally test every protein, but we can trust that number. This is unique.

For language models or image generators, we don’t have that. We don’t have a way to say: “This answer is 80% trustworthy.” That, for me, is the crucial difference. Engineering can reduce mistakes, but it cannot give us that confidence number. And that makes the technology fundamentally unstable.

Some tech leaders have said that AI might be a bubble that will burst. What’s your view?

That’s outside my main area of expertise, but looking at the numbers, it’s hard to believe this level of investment can be sustained forever. Huge sums are flowing into companies like OpenAI and these new mega data centers. Are they making enough money to justify these investments? Are we seeing real productivity gains that match the hype? It’s not obvious.

We’ve seen this before: Big investments driven by short-term expectations, without worrying too much about what happens later. So yes, there are reasons to think the current trajectory isn’t sustainable.

But let’s look at biology and biomedicine. In our field, AI is already delivering concrete results. For proteins, for genomics, it’s not a promise. It’s a reality. So even if some companies collapse under their own economic weight, the scientific community will keep using these models, for example, to decode medical records. That won’t disappear.

Beyond protein folding, what are the most promising use cases for AI in medicine?

There are many, across the entire spectrum, from preclinical biology to clinical applications. A couple of years ago, a paper in Science said: “The next frontier of language models is biology.” And it’s true. More and more AI researchers are moving into biology because it’s scientifically more interesting.

Why? Because biological data has a certain validity, the questions are complex and meaningful, and, importantly, we can test things in real experiments. In other fields, problems are often formalized and less tied to reality. In biology, computational problems are deeply connected to experiments.

The applications are everywhere: genome analysis, protein studies, drug discovery, imaging, and, of course, medical records. Hospitals are already filled with imaging technologies. But the real bottleneck has always been access to large amounts of structured medical data.

That’s changing. When we combine textual data, coded medical records, analytical lab data, imaging, chemical information, and genomic data, the potential becomes enormous.

Cancer has always been at the forefront of AI applications, but now cardiology is catching up. Neurology and mental health are next. Genomic data is now essential in almost every area. Whenever I talk to doctors, they are incredibly curious. Many of them are already using AI-derived tools without even realizing it.

What role does the Barcelona Supercomputing Center play in this ecosystem?

BSC is Spain’s national center for supercomputing. We host one of the three largest supercomputers in Europe. It’s part of a European network, which means scientists from anywhere in Europe can apply for computing time and run their projects here.

Until recently, this was reserved for academic research. But now, with the new European AI Factories initiative, companies can also apply for access. That’s a big change. BSC is also a research institute. We have around 1,500 scientists and engineers, making us one of the largest centers of our kind in Europe. My department of Life Sciences has about 250 people.

We work across all areas of computational biology: data infrastructure, genomics, imaging, protein modeling, small molecules, and disease networks. We’re fully computational and don’t run wet labs, focusing strongly on method development and engineering.

Our primary funding comes from European projects. To give you an idea: after the summer, we submitted 77 grant proposals in the last funding call. That’s how active this field is.

Globally, we see an “AI race” between regions. China dominates patents, the U.S. leads in commercialization, and Europe is strong in science. How do you see Europe’s role?

For the first time, Europe has made very significant investments in computational capacity. With the Gigafactory initiative, we’re talking about €200 billion in co-funding between companies and the European Commission. That’s a lot of money, and it will mean a lot of computing power.

What’s also interesting is a political shift. Europe has decided to collaborate more closely with companies, investing directly in projects that benefit European industry. That’s new.

On the scientific side, Europe is strong, but let’s be honest: all Nobel Prizes are still American. Competing with that level of investment is hard. Even the European Research Council hasn’t been able to double its budget as planned. We need larger investments in science, and we need governments to understand that areas like AI require special programs and funding. Right now, investment levels in Europe are nowhere near those in China, Japan, or the U.S.

There’s also the regulatory debate. Europe tends to regulate before it invests. I’m not against regulation; it’s necessary. But regulation alone doesn’t build capacity. It makes no sense to be the one regulating what others are developing.

Another technology generating excitement is quantum computing. BSC already has a quantum computer. How far are we from real-world applications in medicine?

We have a quantum computer funded by the Spanish government, and we’re waiting for a second one, funded by European money, as part of a continental network of quantum computers.

These machines are still experimental. One important aspect: they are built by European companies. That’s part of the EU’s strategy.

Right now, you can learn how to program quantum computers. You can simulate them. And there are research projects in biology using quantum algorithms: multiple sequence alignment, phylogenetic tree reconstruction, and image analysis. The idea is that once quantum computers become stable, they could be integrated into workflows to address very heavy computational bottlenecks.

Now, if you ask people here at BSC when that will happen, you’ll get two answers. Some say five years. Others say, “Not in my lifetime.” So the honest answer is: we don’t know. Our machines, like most academic ones, are not yet part of production lines. But we are learning. It’s an investment in the future.

Everyone talks about generative AI, but what about classical AI like machine learning, neural networks, and support vector machines? Are they still relevant in medicine?

Absolutely. In hospitals, you’ll still find classical statistics and machine learning in everyday use. If you have a simple dataset, why would you use a massive generative model? A support vector machine may solve the problem perfectly. It’s practical.

You still see plenty of papers published using these methods. They are simple, robust, and effective. Generative AI and deep neural networks are useful for problems that have remained unsolved for decades with classical approaches. But both approaches are compatible. For example, in epidemiology, regression remains a powerful tool. If it works, why complicate things?

Geoffrey Hinton recently expressed deep pessimism about AI. Are you more optimistic or pessimistic?

That’s a discussion we have often here. On the societal level, I see many dangers: election manipulation, disinformation, and the dominance of a few big American companies controlling information flows. People may start trusting anything that looks authoritative, whether it’s genuine or fake. That’s dangerous.

From a European and human point of view, this is very worrying. From a scientific point of view, however, AI is incredibly promising.

I often compare it to nuclear energy. Nuclear energy is dangerous and catastrophic if misused. However, we also use it for good, especially in medicine. We do the best we can with the tools we have while trying to minimize societal-level risks.

That’s how I see AI: a dual-use technology. It can do enormous good, but it can also do great harm.

So, what should Europe and the scientific community do to navigate this dual reality?

We need to invest more. Regulation without investment is meaningless. We also need to build capacity and protect our sovereignty over technology. At the same time, we need to engage society in understanding these technologies, rather than just regulating from above. And we must be realistic about their limitations. AI is not magic.

If this generation of AI is the final stage, then we have a big problem. So let’s make sure it isn’t.

Alfonso Valencia is an ICREA Professor and Director of the Life Sciences Department at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center. He has been a leading figure in bioinformatics and computational biology for decades, with pioneering work in protein modeling, genomic analysis, and biomedical data infrastructures. Valencia has held numerous international leadership roles in research and is a prominent voice on the intersection of AI and life sciences.